There is no doubt that science has come a long way. We have discovered ways to sequence an entire human genome, we have identified around 1.2 million species on earth, and we have put people on the moon. However, when it comes to lichens- the mysterious organism that is a symbiotic relationship between algae, cyanobacteria, and fungi- our scientific understanding is surprisingly limited.

In recent years, the study of lichens has increased by both scientists and citizens alike, aided in part by tools like iNaturalist which has facilitated a growing database and understanding of lichen ecology and distribution. The increased interest in lichens resulted in a significant uptake in donated lichen specimens to the E.C. Smith Herbarium; the current lichen collection has over 5,000 specimens, most of which are from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. While the E.C. Smith Herbarium has historically focused on vascular plants and fungi, the lichen collection is starting to catch up to other catalogued specimens, according to Irving Biodiversity Collections Manager, Alain Belliveau. As one of the “last big frontiers” (Belliveau) in ecological science of non-microscopic species, E.C. Smith Herbarium staff are thrilled to contribute to deepening the understanding of the local lichen community.

Lichens are one of the last big frontiers in biodiversity collections science, especially with regards to non-microscopic species

Alain Belliveau

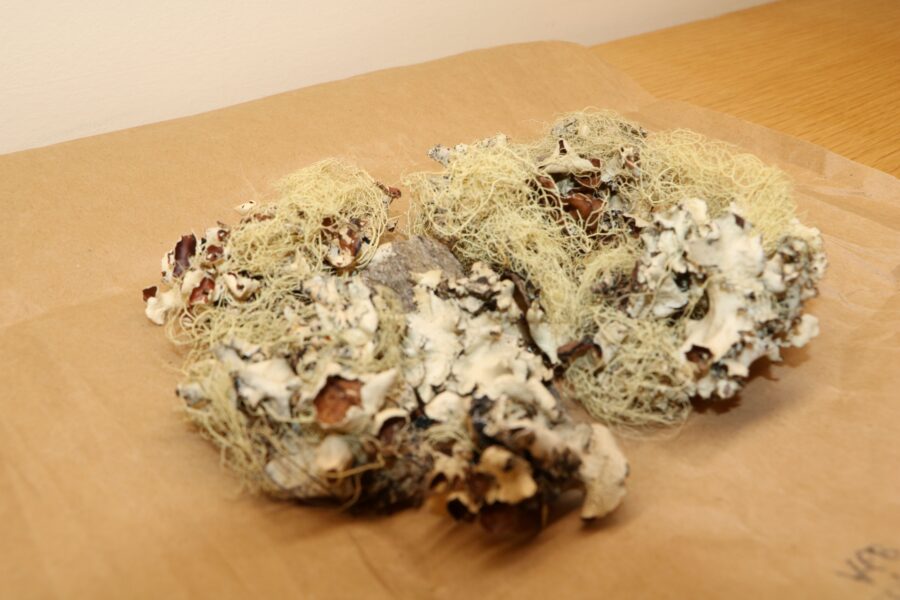

Luna Estrada Perez, an Acadia Environmental Science student and a student in Dr. Walker’s Mycology Lab, is doing her co-op placement at the E.C. Smith Herbarium. A large component of her work is cataloguing the current collection of lichen specimens that were donated to the herbarium from lichen experts and surveyors. So far, Luna has catalogued over 2,000 specimens with the goal of completing another 1,000 by the end of her placement. When asked about her work with the lichen collection, Luna feels humbled by the fact that she is learning about an organism of which the basic biology is not well-understood. Furthermore, the lichen collection at the E.C. Smith Herbarium is important for conservation efforts, as many species of lichen are at risk of extinction. Luna’s collections work will ensure that the lichen specimens are safely stored, catalogued, and published for potential future research that could include DNA barcoding to gain an understanding of lichen at the molecular level. Although 5,000 specimens sound like a lot, Luna emphasizes the need to continue acquiring new specimens every year to monitor changes to lichen health and to continue understanding the ecology and distribution of lichens in this region.

It’s very humbling to learn that we don’t even know much about what’s under our feet

Luna Estrada Perez

Although many aspects of the basic biology of lichens are still unknown, we do know that lichens play integral roles in monitoring the health of various ecosystems. As indicators of ecological and habitat health, lichens are excellent at demonstrating environmental trends. If you’ve ever walked through an old-growth forest and have noticed the types of lichens on the trees are very different compared to those in urban areas, you’ll understand why lichens are excellent indicators of air and rain quality. Thus, lichens are very helpful for identifying places of conservation value, which in turn, helps protect biodiversity.

Additionally, lichens sequester carbon, helping forests capture more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Lichens are also important for other wildlife species, being both a food source and providing structural habitats (i.e. nesting material). The Acadian Forest Region is a unique place to study lichens; due to the various micro-climates in this region, there is a wide diversity of niches, or in other words, the role or function of an organism within a specific ecosystem. This diversity of niches in the Acadian Forest Region leads to more species richness, or the number of species within a defined region, of certain lichen species. Specifically, there are more cyanolichens- lichens comprised of fungi and photosynthesizing bacteria- here than in most other regions in North America. With an estimated 3,600 lichen species in North America and new discoveries being made every year, we are only at the very beginning stages of understanding for this incredible and humble organism. Next time you take a walk in the forest, look out for the lichens and as Luna says, “you’ll start to see them with a different set of eyes”.

So much about lichens is still magic to us, like how they can reproduce in 20+ different ways

Alain Belliveau

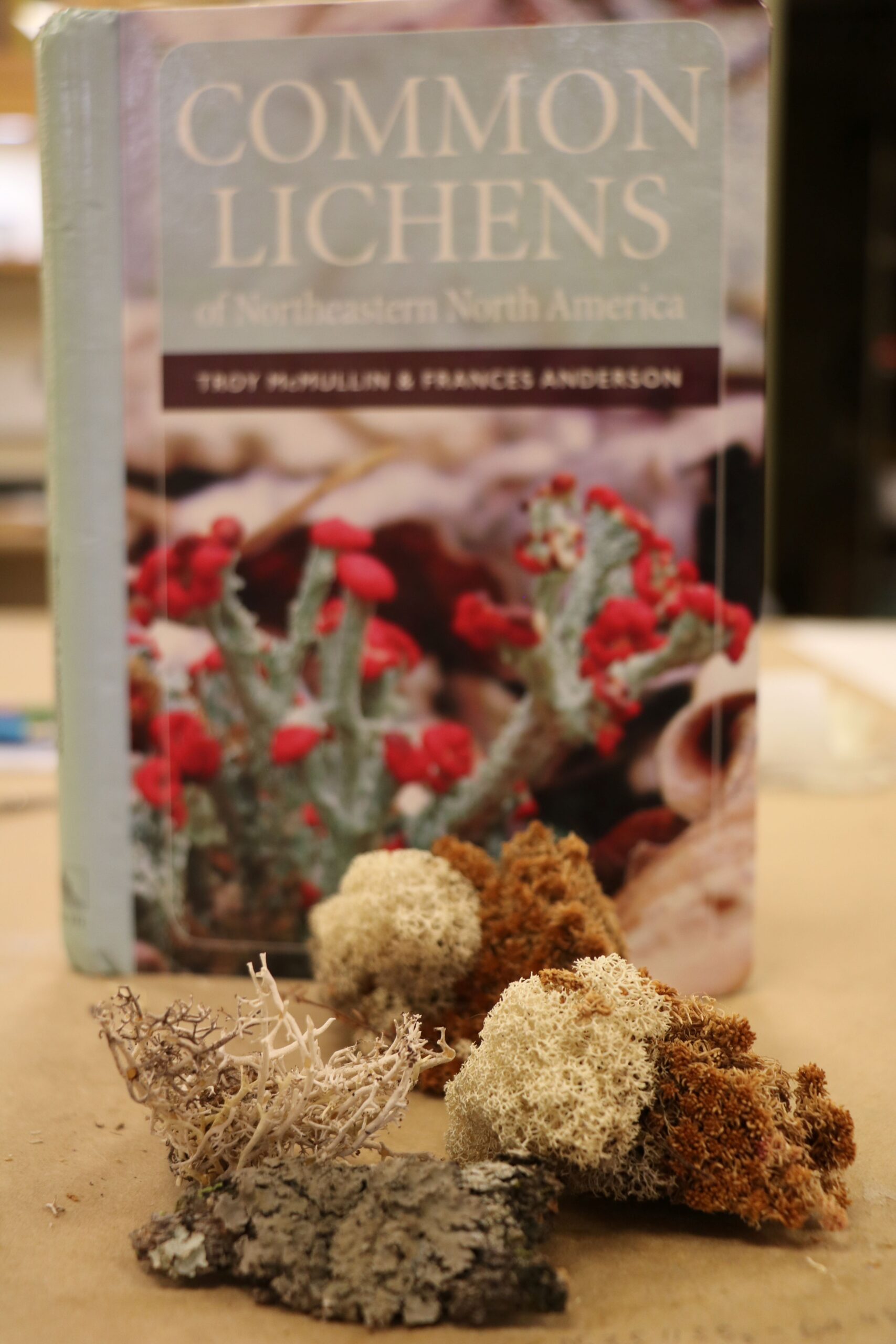

Interested in trying your hand at identifying lichen species? Pick up the “Common Lichens of Northeastern North America” guidebook by Troy McMullin & Frances Anderson from the K.C. Irving Centre café today! Additionally, sign up for a mycology or lichen workshop at the K.C. Irving Centre; check our website for upcoming events.

Acadia University

Acadia University