The adverse effects of climate change such as rising sea levels and an increase in extreme and unpredictable environmental events make headlines in the news almost daily. While increased media coverage on the impacts of climate change means that politicians, community leaders, and the public understand the severity of the climate crisis, the twenty-four-hour news cycle can make us lose sight of the long-term, yet less visible impacts of climate change. One of the long-term but often overlooked impacts of climate change is the mass decline of biodiversity. Human behaviours such as changes in land and sea use, exploitation of natural resources, pollution, the spread of invasive species, and global heating are the main drivers of the rapid decline in biodiversity that our planet is currently experiencing. In fact, species are declining at such rapid rates that some scientists warn of a sixth mass extinction of life on earth.

However, there is some good news. The most recent Conference of the Parties Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) resulted in a landmark agreement to protect 30% of the world’s lands, coastal areas, and inland waters by the end of the decade. While this agreement is significant, there is still uncertainty about how this will be accomplished. What does it look like to protect 30% of the world’s lands, coastal areas, and inland waters by the end of the decade? What does this look like in our own community?

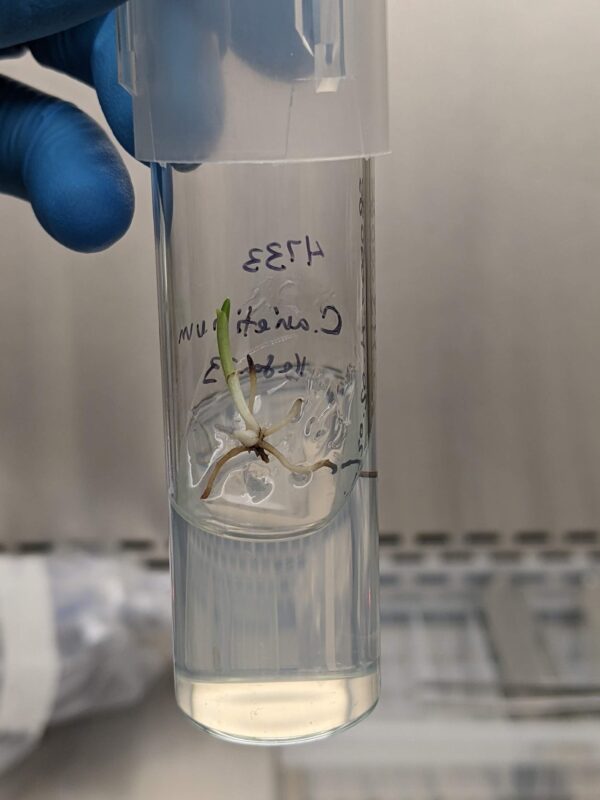

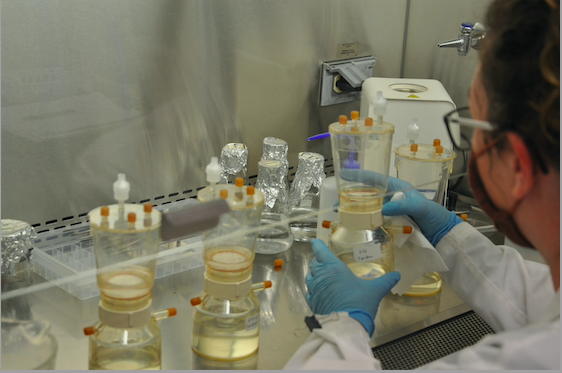

The answer, as you may have guessed, is multi-faceted, complex, and will require collaborative efforts across disciplines. However, when it comes to our own community, student researchers at the K.C. Irving Environmental Science Centre are doing their part to contribute to addressing this global-scale issue. One such researcher is Katie King, a fourth-year honours student in Acadia’s Biology program who is researching techniques to reliably propagate the endangered Ram’s Head Lady Slipper orchid (Cypripedium arietinum) and other native Nova Scotia orchid species. Katie’s research has involved testing techniques that accommodate the specific germination conditions of native, wild orchids to develop reliable propagation protocols for native Nova Scotia orchid species. Part of the challenge with propagating wild orchid species in a laboratory setting is that wild orchids rely on a variety of symbiotic fungi species to germinate. Thus, in a laboratory setting, finding methods to effectively simulate the role of mycorrhizal symbionts in orchid germination is critical. While Katie’s research has focused on the endangered Ram’s Head Lady Slipper orchid, the propagation protocols and techniques that Katie is developing can be applied to other native Cypripedium orchid species as well.

Research like this is crucial for preparing us to take a more involved role in the preservation of these species, and it also better informs us of what these species need and what their role is in their ecosystem

Katie King, 2023

While Katie’s research has focused on laboratory propagation techniques so far, the next steps are determining protocols for out-planting the propagated orchids into experimental garden beds or ex situ environments. Since orchids are sensitive to changes or disturbances, this next step is crucial to increase the survival rate of propagated Cypripedium orchid plants. Particularly given that habitat loss is occurring at ever-increasing rates, finding ways to propagate endangered species like the Ram’s Head Lady Slipper orchid is becoming increasingly important. As Katie articulates, “while protecting habitat is the best approach to preserving native species, having established protocols and techniques for propagating and growing endangered plants is an important alternative course of action for endangered species” (King, 2023).

The most sensitive and usually rare species will be the first to be lost

Katie King, 2023

As Katie articulates, scientists and researchers play a critical role in protecting biodiversity, as “research like this is crucial for preparing us to take a more involved role in the preservation of these species, and it also better informs us of what these species need and what their role is in their ecosystem” (King, 2023). In addition to targeting endangered species, Katie emphasizes the need to understand the intricacies and interconnectedness of ecosystems, including the “less obvious associated species, such as the fungal mycorrhizal symbionts that native orchid species rely on” (King, 2023). Without an understanding of the interrelatedness of species within ecosystems, we may have also “lost our opportunity to protect these systems as a whole” (King, 2023). Sadly, “the most sensitive and usually rare species will be the first to be lost” (King, 2023). Thus, time is certainly of the essence because “we may not get another chance” (King, 2023). Let us use our time wisely.

Acadia University

Acadia University